Editor's Picks

Plant Focus

Oak enthusiasts who visit western Texas often make a beeline straight for places like Big Bend National Park, known for its exceptional localized diversity and rugged scenery. When the looming mountains come into view on the horizon, the anticipation of the botanical riches awaiting in those sky islands builds as the vehicle speeds through a scrubby, less alluring landscape, all the while the excited quercophile is totally oblivious to the extensive stands of one of the more beautiful oaks of the broad region growing inconspicuously right along the roadside.

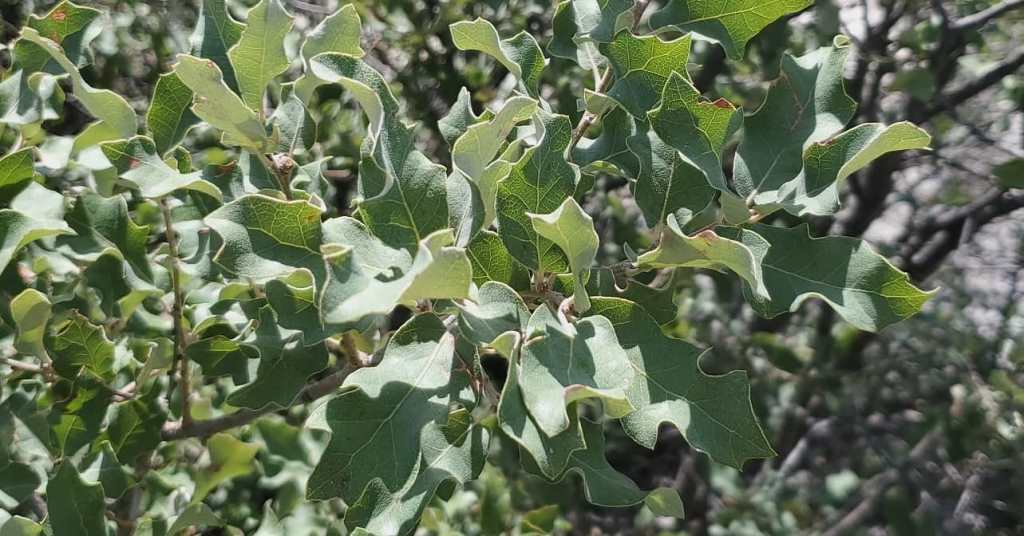

Quercus mohriana (Mohr oak) is in the white oak group (Quercus section Quercus) and is usually a rhizomatous, shrubby species and a specialist of limestone substrates, while the mountains with the higher oak diversity in the Big Bend region are composed mostly of igneous rhyolite. From a distance, Mohr oak colonies are unassuming, shaped by the hostile climate of the region, where rain may be unmeasurable some years. During the extended dry periods, the oaks may look quite rough, but once the monsoonal rains return, these durable scrub oaks will quickly put on a beautiful new flush of fresh blue-gray hairy leaves with white velvety undersides. This foliage will take quite a beating before they start developing a stress patina. If winter proves harsh, the foliage will totally brown and remain attached to the plant, making it look temporarily dead, but assuming the region got a reasonable amount of rain the prior season, it will quickly renew its beautiful coat of foliage in spring.

© Encyclopedia of Alabama, courtesy of the Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of South Alabama

Samuel Buckley (1809–1884)—for whom Q. buckleyi is named—chose the specific epithet in recognition of Charles Mohr (1824–1901), a pharmacist and prolific Alabama botanist in the latter half of the 1800s. The species was first described in 1901 by Rydberg, who adopted the name used by Buckley for this oak in herbarium specimens. There is no indication that Mohr had any direct involvement with the collection or discovery of this species, and therefore he is merely being honored by a fellow botanist. Though Buckley was the state geologist for Texas, he was very much involved in botanical work throughout the southeastern US where he developed respect for Mohr’s focus on the flora of Alabama.

Though rhizomatous, the colonies of root suckers usually form a dense, attractive clump averaging 1.5–2 meters tall, and one plant may span many meters in diameter. At some sites, colonies tend to be short (<1 m), and at others, there may be a single dominant stem with a wide, dense crown to 3 meters tall, and at most a minimal amount of suckering around the base. Texas ranchers often refer to these as “shin oaks” due to their shin-high stature, but unfortunately that common name gets applied to several other low spreading species around the state.1 Still at other sites, growth habits vary wildly. One intriguing site on private land in Terrell Co. Texas has large, single-trunked trees to at least 8 meters. Genetics and/or site conditions surely play a role in these varying appearances.

The foliage on this species is also highly variable within a single population, both in shape and color. Though the lower surface is always covered in thick, clean white indumentum, the top surface can be blue-gray, olive, to dark green in color, noticeably accentuated with a dusting of light-colored stellate hairs. The hairs may be sparse, or in some cases quite dense to the point where they make the leaves look silvery-white with little to no green showing through. Some leaves may be ovate, others oblong, and occasionally quite narrow-elongate with either pointed or rounded tips. Margins can be sparsely or heavily toothed, especially on the distal third of the leaf, while others are totally lacking any marginal dentition. Leaves can be either flat or undulate to a point where they are heavily curled, which helps flash the beautiful contrasting white undersides.

Despite its unrelenting growing conditions, Q. mohriana is one of the more reliable acorn producers. Even in exceptionally dry years, when many oak species of the broad region may not produce at all, it is possible to find at least a small number of acorns maturing fully, providing critical food for wildlife during a tough seasonal transition. The acorns are usually solitary to paired on short peduncles in drier times, but during good monsoonal years some individuals may produce them in clusters of three or more on longer peduncles. The variably-sized acorns vary from egg-shaped to narrow-fusiform and sometimes globose, and the robust cupules are roughly scaled and covered in white pubescence.

Putative natural hybrids exist with Q. grisea, which grows on igneous soils nearby, and possibly Q. vaseyana and Q. pungens which can sometimes be found growing near or among colonies of Q. mohriana. Some of the morphological variability outlined above may reflect influx of genetics from these species over thousands of years.

Though focused on here specifically in the Trans-Pecos, Q. mohriana ranges further north wherever limestone substrates are exposed through the Texas panhandle with a few isolated populations cropping up in eastern New Mexico and western Oklahoma. It also ranges south into adjacent parts of Coahuila, Mexico. Good places to see them in western Texas are wherever roads cross the Glass Mountains, one of the few extensive limestone-based mountains in the region. They can also be spotted along Interstate 10 in the western extent of the Edwards Plateau just east of the Pecos River.

Currently cultivated in only a few botanic gardens and private collections, it seems slow growing and often remains a single-trunked shrub for a long time before it begins producing a few suckers. Still, with some patience it can turn into an attractive, low-maintenance shrub for xeriscapes and otherwise well-drained conditions and should be trialed more. With good drainage, collections from western Texas are surviving in the more humid eastern U.S. in USDA Zone 7, and it naturally ranges into zone 6 and could very well prove to be a bit hardier.

1The are two theories regarding the origin of the term "shin oak": as a reference to the shin-high stature of the plants, or as a deformation of "shinnery oak", another name for shrub oaks in the U.S. West and Southwest, especially Q. havardii. "Shinnery" is thought to have evolved as a modification of Louisiana French chênière, from French chêne ("oak").