Editor's Picks

Plant Focus

When it comes to mythology, mysticism, and religions, oaks have been, and still are, the most important trees for the Serbian people. The roots of worshipping oak trees come from the Slavic, pantheistic period (Sofrić Niševljanin {1912} 1990), and they have prevailed until today. Old oaks are often sacred trees in villages and hamlets. However, young oaks also have an important role as part of Christmas customs. In every house, a young oak tree is used as a бадњак (badnjak), a ceremonial tree, which the people refer to as a person rather than a tree (Čajkanović 1973). The badnjak tree is gathered in the morning or afternoon on the 6th of January (Christmas Eve in the Julian calendar), depending on the region (Popović 1989; Trajković 2005) or even on the 2nd of January in Luštica (Bay of Kotor, according to Vučinić-Nešković 2008). In villages all over Serbia, it is still a living custom for people to cut down their own trees, while in cities, badnjaks are usually bought in the street markets. Usually, the elders in the family cut the tree. Once the oak is cut down, they would say some short prayers and pour some wine and rakia (fruit brandy) on the stump together with some bread and corn. The chips of wood that come off the tree during cutting with an axe are taken back home as they are an important part of tradition to ensure wellbeing during the following year. It should be noted that all the mentioned customs may vary substantially between regions or even villages, and this account is just from my personal experience.

Photo: Lazar, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

According to Trajković (2005), the choice for a tree to cut down is between a Quercus cerris and an “oak”. The term “oak” (храст, hrast), may mean any other oak species besides Q. cerris, such as Q. robur, Q. frainetto, or Q. petraea. The reason for this is the fact that Q. cerris is a widespread oak that can grow in association with any of the oak species mentioned above, as it shares habitats with all of them. Thus people from different regions often distinguish only Q. cerris, which they have a specific name for, i.e., цер (tser), and храст (hrast), which basically means “the other oak in the forest.”

On the 6th of January, everyone can cut down their badnjak tree wherever they want, even on other people’s properties (Trajković, 2005). It should be noted that there are some exceptions when it comes to species selection: in Luštica (Bay of Kotor), olive trees are commonly used as badnjak trees (Vučinić-Nešković, 2008). Once the badnjak is cut down, it is used as decoration in front of the house and other objects, and even on cars (Trajković, 2005). In the evening, a badnjak tree is burned in every household and in churches. Badnjak can be understood as an equivalent to the Yule log, which is also burned in other European traditions (Vučinić-Nešković, 2008).

Photo: Ranko at sr.wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0 RS, via Wikimedia Commons

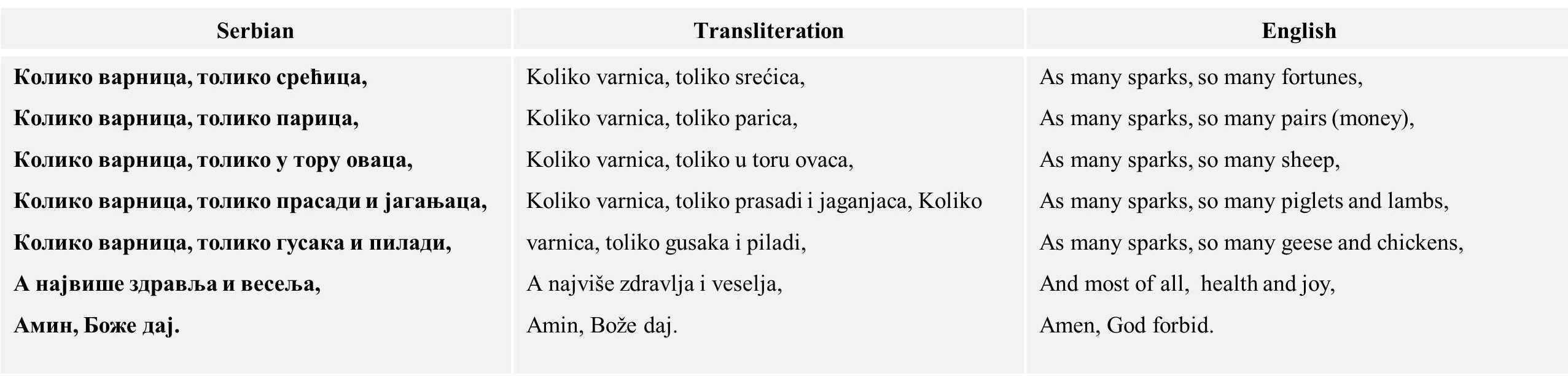

Before the badnjak is burned, the stem should be divided into three parts. Honey should be put on top of them so that members of household can taste some of it to have a “sweet year”. Two of the three stem sections are burned the same evening by the members of the household, and one on Christmas morning (January 7th) upon the arrival of the first guest, called положајник (положајник, položajnik), who receives a special gift from the family. When the oak is put in the fire, the person doing so should strike the piece of wood on the fire repeatedly to make as many sparks as possible. While tapping the fire with the badnjak, they chant the following:1

The main meaning of the chant is that the more abundant the sparks, the more the happiness, money, and above all joy there will be in the household. In the past, more sparks could mean a wish for more chickens or sheep for the family, but in the present day, one may wish for other things as well.

The young oaks cut down are usually growing in dense thickets, so their cutting should not do any major harm to oak forests. On the contrary, it may even be beneficial as it resembles silvicultural cleaning.

Works cited

Popović, M. 1989. The Serbian Customs in Suvi Do 1. Novopazarski zbornik 13, 183–191

Sofrić Niševljanin, P. (1912) 1990. Glavnije bilje u narodnom verovanju i pevanju kod nas Srba po Angelu de Gubernatisu. Belgrade: Beogradski izdavačko-grafički Zavod.

Čajkanović, V. 1973. Mit i religija u Srba. Edited by Vojislav Đurić. Belgrade: Srpska književna zadruga.

Trajković, I. 2005. Christmas Customs in Niš and Surrounding Area. Glasnik Etnografskog muzeja u Beograde 69, 31–45

Vučinić-Nešković, V. 2008. The Stuff of Christmas Homemaking: Transforming the House and Church on Christmas Eve in the Bay of Kotor, Montenegro. Issues in Ethnology and Antrhopology n.s. Vol. 3, no. 3, 103–128

1Text taken from the website of Serbian Orthodox Church www.spc.rs/sr/bozic.